The promise of quality digital learning for all students

October 30, 2020 | By Lynn Armitage

When Annalee Good, an educational researcher and evaluator from UW-Madison, and her colleagues began studying the use of digital tools in classrooms a decade ago, they never imagined that a global pandemic would drive the adoption of at-home online learning at warp speed.

COVID-19 has caused a dramatic, sweeping change to education. Whenever students and teachers fully return to in-person classrooms, school districts must take a critical look at the role of digital tools and decide how to move forward. Schools must be vigilant to ensure their online learning systems contribute to the equitable education and academic outcomes of all students, particularly the historically underserved.

A recently released book―written, interestingly, prior to the outbreak of COVID-19―“Equity and Quality in Digital Learning: Realizing the Promise in K-12 Education,” offers specific strategies and recommendations on how to do just that.

The book and supporting website are the result of 10+ years of research in the Milwaukee and Dallas public school districts by co-authors Good, a principal investigator with the Wisconsin Center for Education Research, Carolyn Heinrich of Vanderbilt University and Jennifer Darling-Aduana of Georgia State University. They lead a team of researchers, which includes Huiping (Emily) Cheng and Lisa Geraghty, also of WCER. The research has been supported through funding from a number of sources, including Mr. Jaime Davila, the William T. Grant Foundation and the JPB Foundation.

How to create a solid digital learning strategy

As Good explains, a successful digital learning initiative is not about spending a lot of money on laptops or Kindles. “Many factors essential to ensuring success of digital learning initiatives have less to do with the capabilities of the technology and more to do with how it is enacted in the classroom and other educational settings.”

In the book, published by Harvard Education Press, the researchers highlight four “leverage points” that school districts and educational organizations should focus on to implement equitable digital learning programs:

- Structure policies, contracts and budgets to be transparent, especially to make sure access to resources is equitable.

- Strengthen the capacity of educators to implement digital initiatives through targeted and continuous professional development.

- Create student-centered, responsive content and instruction. For example, engage parents and students as partners in designing the curriculum.

- Build the capacity of organizations to support research and evaluation, including engaging students, families and classroom teachers as active parts of the process.

Digital learning initiatives can work, but it is not a one-size-fits-all situation, says Good. “Unfortunately, a lot of school districts see what another school district is doing and think they can just plug-and-play the same strategy, but it is not always a good fit.” Good, co-director of the Wisconsin Evaluation Collaborative and director of the WCER Clinical Program, advocates for careful planning, monitoring and rigorous assessment of digital learning at district, school, classroom and student levels.

“Without adequate planning, new digital technologies may add up to little more than costly distractions,” the authors write in a working paper, citing a statistic that schools in the U.S. spend nearly $8 billion a year on education software and digital content.

Teach the teachers!

One of the key takeaways from this digital learning research is the importance of focused instruction and feedback with teachers who have had adequate training in the use of technology. The researchers recommend that school districts prioritize the professional development and technological support of teachers in their digital learning plans.

A nationwide survey by Common Sense Media published in 2019 by EdWeek reports that 31 percent of educators say they are not able to use technology in their classrooms because of a lack of training. School districts would be wise to reverse that trend, as the research by Good and her colleagues shows that students who received real-time digital instruction from well-prepared teachers performed better in math than students who learned only from software.

But now with many K-12 schools in the U.S. offering remote learning this fall to help tamp down the spread of COVID-19, how does teacher instruction factor in? “In this current COVID context, family members literally are co-teachers. This then makes us have to think really differently about building the capacity of family members around digital learning, which is made even more complex when we think about all the other things family members have going on,” says Good.

To support parents and family members who have had to become at-home teachers for children during the pandemic, Good points to helpful suggestions on the William T. Grant Foundation website, one of the key funding partners for this digital learning initiative.

Expanding learning opportunities through telepresence

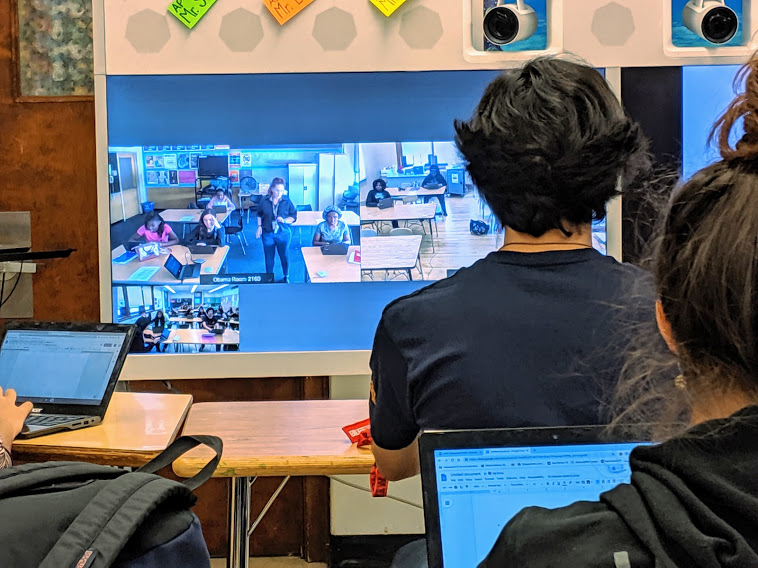

Through telepresence, students at Bay View High School, Washington High School and Barack Obama School of Career and Technical Education study AP World History together in the Milwaukee Public School District.

For five years, Milwaukee Public Schools has been at the forefront of digital learning through telepresence―real-time classes taught by real teachers in a real classroom setting, but made available to students in remote settings through digital tools. The benefit of telepresence is that many other students also attend the same class remotely from various locations in Milwaukee. Huge digital screens and high-quality tracking cameras with speakers installed in the originating classroom make it seem as though everyone is sitting together in the same room. Students can see one another and interact on screen.

“The greatest benefit of telepresence is that we are providing learning opportunities for students who would not otherwise have had that opportunity due to limited class sizes and course offerings at many schools,” says Neva Moga, MPS’ instructional technology supervisor. She says MPS began using telepresence because the district was not able to offer many advanced math courses for all schools, putting college-bound students at a great disadvantage.

Twelve schools currently participate in the MPS telepresence program, from 7th to 12th grade. Telepresence courses include Japanese, ethnic studies, honors algebra, environmental science, mobile apps and AP courses in statistics, literature, government, world history, psychology, Spanish and calculus. The maximum number of schools for any one course that can be connected through the MPS telepresence program is three.

Good says that using telepresence to teach AP courses is a great example of how digital tools in the classroom can better equalize learning opportunities for all students. But as she referenced earlier, effective digital learning programs require adequate training for teachers, and that is exactly what Suzanne Loosen does.

As the telepresence teacher leader for MPS, Loosen provides professional development and support for teachers and facilitators. “I help train teachers in the telepresence technology, coach them one-on-one, share best practices and travel every day to classrooms and check in with students to see how it’s going.” Loosen says that each telepresence class has one certified teacher who teaches the course and a paraprofessional who facilitates on the other side of the camera, delivering materials to students, encouraging participation and helping with whatever is needed.

Moga says the MPS telepresence program has been worth the investment of time and resources. “Our research shows that during the first three years of the program, the ACT scores of participating students increased.”

Not only are MPS telepresence students gaining valuable access to advanced courses, but they also enjoy the social aspect, shares Loosen. “We really highlight relationship-building as one of the tenets of the program. Not just for teachers, but for students, too.” Even though they attend different schools, Loosen says students form genuine friendships. “They will see each other at sporting events and say, ‘Hey, I know you!’ A lot of times they will exchange social media information and become friends online.”

Moga credits the research partnership with WCER for “giving more legs” to the district’s telepresence program. “Thanks to our partnership with Annalee, our proof of concept is not just anecdotal. The quantitative data they collected shows that the program is doing what it sets out to do.”

WCER and MPS: Partners through the years

This enduring research-practice partnership with Milwaukee Public Schools began in 2006 when MPS reached out to WCER to help evaluate some of its programs. For nearly 12 years, Sandy Schroeder, MPS’s now-former manager of extended learning, worked closely with Good and Heinrich on integrating several high-profile education initiatives into the district, such as online credit recovery through Edgenuity, an online learning program that uses technology to provide coursework and improve student outcomes.

Schroeder says her partnership with WCER has been unique. “Instead of the research partners telling us what they want to do, our partnership with Annalee and WCER has been one based on mutual trust and collaboration.”

Schroeder explains that Good and her colleagues have always structured her research around MPS’s goals and what was best for their students. “Once her research was completed, we always had actionable steps from the findings to implement change, and to better our practice for students and the district.”

This past March, after COVID prompted schools to close across Wisconsin, Schroeder retired her post at MPS. But the work she started with the research partnership goes on with a project yet to be completed: the redesign of an online citizenship course in the district to be more culturally and contextually responsive.

“I see this as a continuing project for the next few years because it is going to take a while to modify the course and monitor it,” predicts Schroeder. “But I cannot reiterate enough how beneficial our partnership with Annalee and WCER has been so far for the Milwaukee Public School district.”

Good concurs that partnerships are key to successful education research. She is especially grateful for the generous funders who have supported her work along the way.

Recently, her partnership with Heinrich, Darling-Aduana, Cheng and others has earned national praise. The American Education Research Association (AERA) has honored this research team with the Palmer O. Johnson Memorial Award for best 2020 journal article, “A Look Inside Online Educational Settings in High School: Promise and Pitfalls for Improving Educational Opportunities and Outcomes.”